Over the holiday’s I finally got time to read D. Casey Flaherty’s ‘Unless You Ask: A Guide For Law Departments To Get More From External Relationships‘ published by the Association of Corporate Counsel (ACC).

Casey’s publication is excellent and very insightful. Although written for in-house legal departments, it contains information that every private practice lawyer should be across. If for no other reason than it has an array of sample questions they may be asked.

But, it is a brief piece in the publication on asking for discounts on hourly rates/bills that I wanted to share with you all. Because Casey has managed to put into words, both succinctly and comprehensively, my own feelings on discounts.

So here it is (see pages 64 & 65):

Without some grounding in value, discounts just become a game.

First, you can only push the discount lever so many times. A recession hits or you run a convergence initiative. You get your firms to take a big haircut. What’s next? It will probably be a few years before you can return to that well in any meaningful way. Continuous improvement, on the other hand, should be a constant. There is always some process to refine, some assumption to question, or some technology to take better advantage of. Discounts can be part of a strategy. But a strategy that relies entirely on discounts is hollow.

Second, there is a huge volume of data that suggests that while most clients see themselves as negotiating progressively deeper discounts, what they are really doing is negotiating down the size of the rate increase. Last year, the client got a 10% discount off a $500 rate. This year, the client gets an 11% discount off a $520 rate. What really happened is that that firm increased the rate from $450 to $463. You can perform this trick—4% rate increase, additional 1% discount—for a quite long time before the rate flattens out. How long? 66 years. In 2081, the paid rate ($1,600/hr) would finally stop increasing as the discount (75% off a published rate of $6,399/hr) caught up to the rate increase.

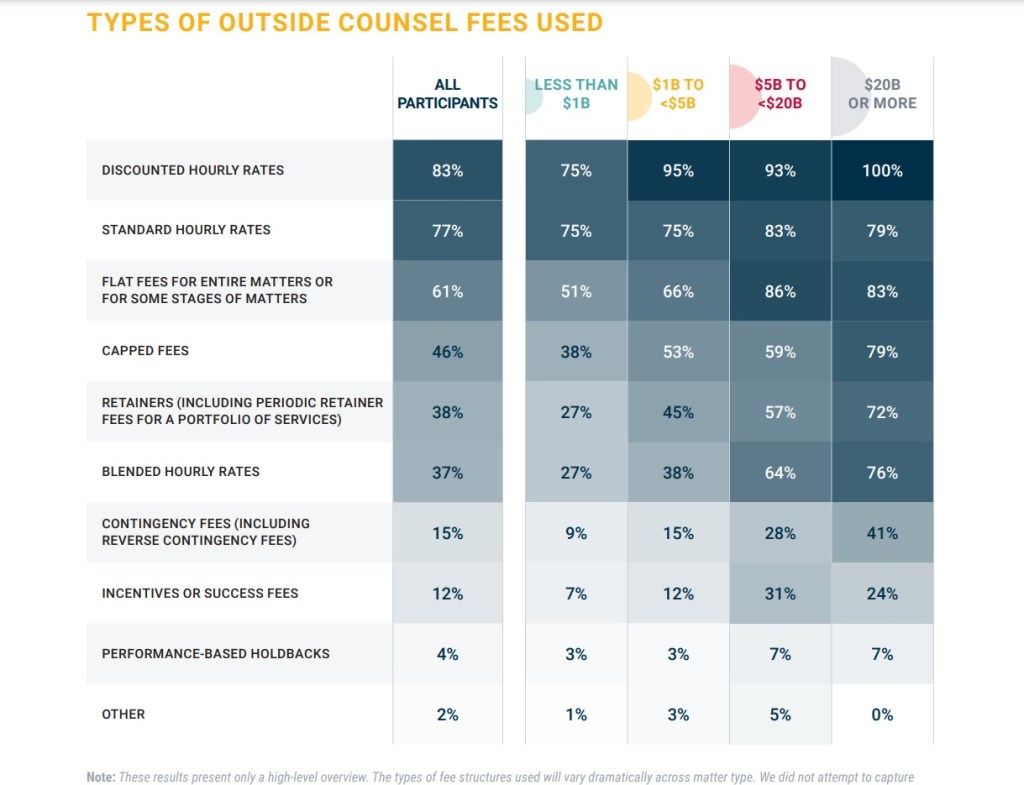

Third, while almost every law department will proudly refer to the deep discounts they’ve negotiated, only about half even get one. That’s because a true discount is not calculated versus a lawyer’s published rate—of which there may be several—but is calculated by reference to something called a standard rate, an internal firm number used to determine realizations, profitability, etc. With a few exceptions, almost no one pays published rate and therefore everyone thinks they are getting a discount. But only about half of clients actually pay below standard rate. And even they are not getting as deep a discount as they think.

Fourth, if you count discounts as savings, please stop. If you’ve reduced rates below what you were paying previously, that’s one thing, especially if you also have a mechanism to monitor and hold the line on hours. But if you are just counting the delta between the published rate and your paid rate, it introduces some bizarre incentives. It encourages firms to jack up published rates so they can offer you the optical illusion of a bigger discount. It encourages you to select higher priced firm so you can report greater ‘savings’—i.e., you show double the savings by paying $700/hr to a lawyer with a published rate of $900/hr than you do paying $350/hr to a lawyer with a published rate of $450/hr. And your savings accumulate with every extra hour of work the firm bills. There is something inherently perverse about a savings metric that makes you look better the more you spend.

Fifth, finally, and most importantly, undue emphasis on discounts tends to confuse unit price with total cost. Rate differences are linear. Hours can differ by orders of magnitude. The $350/hr associate might look relatively cheap until it takes them ten hours to deliver work half as good as what the $800/hr partner delivered in one. Attention to the unit price ($350 v. $800) will obscure both quality and total cost ($3,500 v. $800). We intuitively understand the difference experience can make. Systems—the proper integration of process and technology to augment expertise in delivering legal services—are experience institutionalized. Systems merit attention in trying to understand the relationship among quality, unit price, and total cost. Discounts are only a small fraction of one piece of that puzzle.

There you have it: why discounts should not be anywhere near the front of your pricing arsenal.

RWS_01