A lot has been written about a need to kill the billable hour. Some of it has merit. Lots of it doesn’t. Some of it has been written with the client’s benefit in mind, most of it hasn’t – in the it is written with law firm survival in mind.

Crucially, pretty much all of it is irrelevant.

How can I be allowed to say such a thing?

Because the reality is that under most law firm’s current performance regimes, we actively encourage the survival of the billable hour, even while we advocate for its death.

What do I mean by this?

Well, as I alluded to in my post last week, what consistently surprises me is that while many advocate for the death of the billable hour, with few exceptions most of these advocates fail to look at one of the principal underlying issues that makes its death – overnight or otherwise – near impossible:- utilisation.

‘Utilisation‘ refers to the metric by which we determine how busy fee earners are. In most firms (although not all), to ascertain ‘utilisation’ we look at the annual budget of hours the firm has set the relevant fee earner (typically starting at 1,400 hours and going north) and we measure that against the amount of billable time they have put on their time-sheets (daily, weekly, monthly or annually). From this, we then decide how “busy” that fee earner has been.

But, it’s actually a crock of shit as a metric of measurement.

Why?

Because, it doesn’t tell us how much time the fee earner has worked on the business – e.g., KM time (typical requirement of an additional 40 hours) or pro bono time (maybe another 40+ hours – notice the reoccurring hour theme here?).

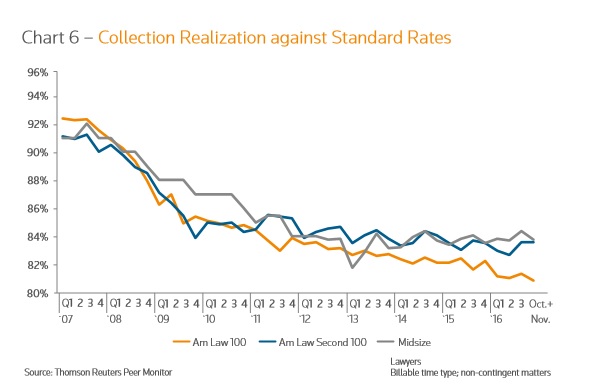

It doesn’t even actually tell me how busy the lawyer has been, heard of “desktop discounts” aka “leakage”.

But most important of all, it doesn’t tell me if you made any money at all, much less any profit!

What it does is assumes that you get 100% of your hourly rate paid – but as we have seen the reality is far from the truth insofar as that assumption goes.

So it’s an absolutely rubbish metric in my opinion.

But, and I kid you not when I say this, utilisation will determine the pay rise and bonus of pretty close to every lawyer (and by that I mean partner down) in Australia this year.

So, if we except that utilisation is a rubbish metric: why does it persist?

The answer to that question is, in my opinion, one of the principal reasons why we will never get rid of the billable hour under the current reward and benefit system – because it is perceived as being a fair metric of comparison.

“What”, I hear you cry, “that’s madness!”.

But it’s true. In the modern ‘full service’ law firm, where billable hour rates vary according to the type of work we do, how busy we are is seen as a fairer metric of comparison than the rate we charge or the amount we earn – with the number of hours we work, Goddess of all.

So how ridiculous is all this really?

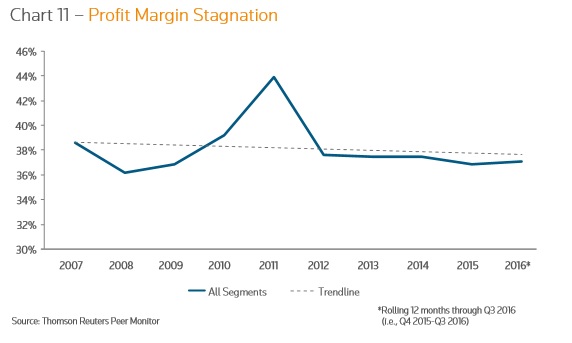

Well, in most firms as a lawyer working on the billable hour I’ll be better paid (including bonus) with 150% utilisation, 80% realisation and 15% net profit margin, than a lawyer working on fixed fees with 80% utilisation, 150% realisation and 40% net profit margin.

I’ll leave you to decide the madness of that.