Last week (22 February 2024) Thomson Reuters Institute published its midyear market update on Australian law firm’s financial performance. Overall the sector remains robust, posting year-on-year “growth” of 7.2%. “Growth” here being defined as:

A measure of total billable hours worked by the average law firm

Leaving aside the flaws in that definition, if we are to use it as a yardstick for year-on-year growth and a like-for-like comparison globally, then the Australian legal sector looks positively healthy – particularly so for those practising Dispute Resolution (9.5% growth year-on-year, although I question the low starting bar here as DR has suffered a number of negative years as a result of COVID) and “General” Commercial (7.5% growth year-on-year; and while no definition of “general” is provided it clearly doesn’t include M&A, which sits in a different bucket).

Black clouds?

If there is a black cloud around the numbers it’s leverage and expenses.

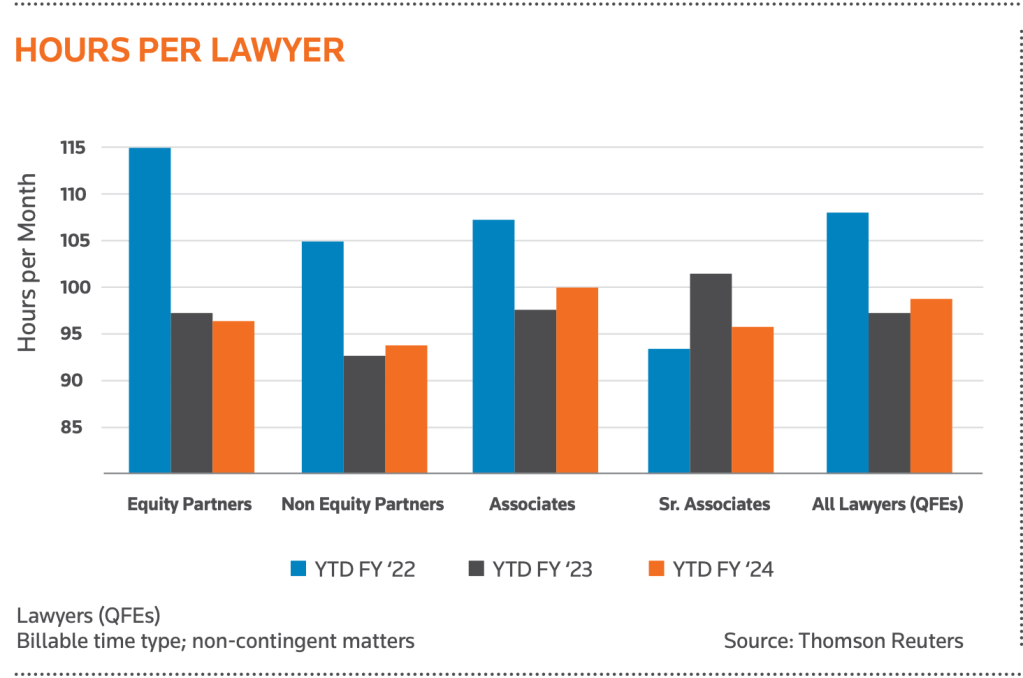

As the chart above indicates, leverage between partners, senior associates, associates and lawyers still looks out of shape when compared against firms in other jurisdictions.

What this chart indicates to me is that partners (in particular, equity partners) are still doing way too much of the billable work and not pushing the work down to more junior lawyers (which might be understandable if it was salary partners looking to make equity; but kind of suggests it is equity partners looking to retain equity points – maybe a post for another day!).

Having said this, it might also be a trait of the Australian legal market. We often don’t follow the 10-20-30-40 leverage model here in Australia.

A potential second black cloud is on the expense-side: lawyer renumeration.

While this appears to have cooled – down from 13% growth in 2023 to 7.3% growth in the first half of 2024, for those of us who work in this market day-in, day-out, there is an acknowledgement and acceptance that mid-level lawyers (those between 4 and 8 years PQE) are rare as hen’s teeth.

And the reason for that is simple – most see Australia as a small fish bowl and want to spread their wings in Asia, London or New York.

Who could blame them!

Some come back, many don’t.

But what it does mean is this: we pay a premium for mid-level [good] lawyers here in Australia!

The last black cloud has to be lateral partner movement.

The Thomson Reuters midyear market update doesn’t include a section on lateral partner movement, but it should. Not only because it would make for interesting reading, but also because it’s a good indicator figure.

As always, get in touch if you want to talk through any of the above.